Shelves weigh heavy with the anatomical art of the past thousand years. Plate by plate, detail by detail, artists rendered the three-dimensional anatomy of human figures on two-dimensional surfaces.

Such works reveal more than meets the eye, according to artist Libby Reuter. Although some may see these old renderings as sacrosanct revelations of absolute science, or at least travelogues of journeys toward truths about the body, Reuter says that those artists encoded themselves — their beliefs, understandings and misunderstandings of what they thought they saw.

Or wanted to be seen.

Reuter intends to re-engage viewers with those classic anatomical presentations through her exhibit of large-scale drawings and digital images, “Anatomical Re-presentations,” which opened at the Farrell Learning and Teaching Center at 5 p.m. on February 20th, and runs through May 15th.

Reuter is executive director/curator of the William & Florence Schmidt Art Center at Southwestern Illinois College in Belleville, Ill. Previously she served as a faculty member and administrator at Washington University School of Art.

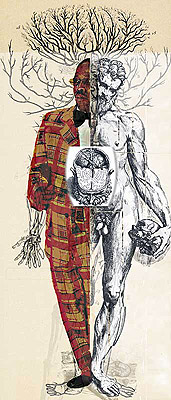

In her art, Reuter layers contemporary imagery over old anatomies in order to enhance or to intentionally obscure the forms. Along with the visuals, she inserts fragments of philosophical and scholarly texts that shape one’s responses to the body.

Reuter says she explores the ways we create a “self” by combining our internal sensory and bodily experiences with images received from other people. “I’m interested in seeing how bodies get represented, what assumptions people make when creating anatomical art.”

Her circuitous route to this subject matter came by way of a trip to Europe. There, elaborate religious reliquaries containing bits of preserved tissue got her thinking about our interior spaces — “the revered parts of our bodies that can be also seen as ugly and that often we don’t like to think about.”

Next, she viewed anatomical wax models at La Specola in Florence, Italy. Created as teaching tools, these three-dimensional studies might seem rather objective. But Reuter vividly recalls her response to the serene beauty of the female bodies’ translucent wax skins juxtaposed with their shockingly exposed internal organs. This simultaneous display of inside and out, and the mixed emotional reactions it generated in her, became an impetus for making art.

In addition to medicine, science and philosophy, Reuter found inspiration in the psychology of Carl Jung, who saw individuals engaged in a process of integrating the Real, the Ideal, the Mirror and the Shadow selves. Reuter thinks this mirrors the parallel roles of the early anatomists. They depended on a cadaver (usually an executed man); an anatomist who didn’t touch or look at the body but read from a revered text (frequently Galen); a demonstrator who did the actual cutting; and the media (the artist who recorded the scene and the engraver who prepared the drawing for publication).

According to Reuter, these roles compare with Jung’s ideas of selves. The corpse is the real human body; the anatomist is focused on the ideal; the artist/engraver is the mirror reflecting the physical body through the lens of contemporary beliefs, technology and graphic styles; and the demonstrator exemplifies the darker, shadow side—the visceral experience of the body’s interior, death, punishment, and criminality. A series of digital books in display cases will compare the Jungian archetypes with historical anatomical illustrations.

Hours poring over the pages of dusty medical texts showed Reuter how representational schemes — use of certain colors or labeling systems — readily date anatomies to a specific era.

Likewise the belief systems of an era can also date the work. Reuter is especially intrigued by a Leonardo da Vinci drawing of the interior of a heart. Although the drawing faithfully conveys the structure of the chambers, some additional curious sketchy lines don’t seem to fit the facts, in contrast to Leonardo’s typical optical fidelity. This, Reuter thinks, shows the pervasive influence of Galen’s teachings about heart anatomy. It is as if the drawing captures the empirically focused da Vinci’s struggle to see parts that Galen said should be there.

“What we think we’re going to find and what we sometimes actually find are two different things,” laughs Reuter.

Reuter relishes this opportunity to show her work before a panel of “experts” — the School of Medicine community, many of whom have first-hand knowledge of the body’s inner forms. “And hopefully people can recognize some of my reference images,” she says.

“I look forward to feedback from students and faculty about the meanings these works re-create for them,” says Reuter. “And because all art is a reflection of the ‘self’ that created it, I am the corpus — but gratefully not the corpse — being examined in this body of work.”

This exhibit is presented in collaboration with Art St. Louis. For more information on this and other Farrell Center art displays, please call (314) 747-3284.