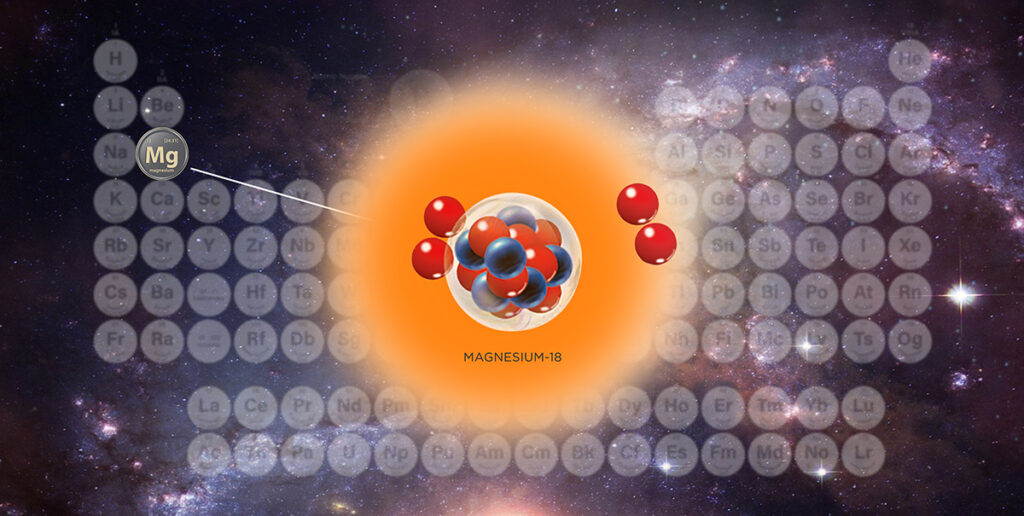

A new isotope of magnesium — magnesium-18 — was discovered by a team that includes Robert Charity, research professor of chemistry, and Lee Sobotka, professor of chemistry and of physics, both in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

This project was spearheaded by Chinese researchers at Peking University and by Kyle Brown, assistant professor of chemistry at Michigan State University. Brown earned his PhD at Washington University in 2016. The discovery was reported Dec. 22 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Magnesium is the eighth-most abundant element in Earth’s crust. Studies of magnesium have provided insight into exotic decays and the evolution of nuclear shells that dictate nuclear stability and nucleosynthesis.

While Charity and Sobotka always find the discovery of a new isotope exhilarating (this is their fifth such discovery), they said they are motivated to complete this research because of what it reveals about the nature of quantum states near decay thresholds.

“Decay is how the states are actually detected,” Sobotka said. “But the processes that are the inverse of the decay allow for element building: the synthesis of elements and energy conversion processes.

“In this effort we have found dozens of new levels and determined their energy widths (inversely proportional to their lifetime), spin angular momentum and a quantity called parity,” he said.

Forged at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory at Michigan State University, the new magnesium isotope is so unstable, it falls apart before scientists can measure it directly. Yet this isotope that isn’t keen on existing can help researchers better understand how the atoms that define our existence are made.

Read more from Michigan State University.