Talie Johnson, BFA ’23, grew up on a six-acre farm in Belvidere, Illinois, surrounded by large neighboring cornfields. On her family’s property, wild grasses grew aplenty, and Johnson would often hang about in their midst, admiring their wispy surfaces, breathing in the fresh air and generally adopting the pace of nature.

As a communication design major at WashU, Johnson spent a great deal of time indoors seated in front of a computer. Then she enrolled in a “Sustainability Exchange” course with a focus on Forest Park. Over three semesters, she and 30 other students roamed the park to experience firsthand the often overlooked and understudied urban biodiversity there. One crisp morning in fall 2022, for example, Johnson found herself in the park’s fish hatchery area, lying on her belly among a patch of cypress knees, admiring their oddly shaped beauty and looking for the most interesting angle to snap a photo.

If Johnson’s image was compelling enough, it could vie for a spot in the coffee-table book she and her classmates have been producing as the course’s final project. The 150- to 175-page book features original student artwork, stories and poems, photography, historical and species accounts, and more. As the book’s designer, Johnson’s been working closely with Joe Steensma, who taught the “Sustainability Exchange” course, to complete the layout. [At press time, the two hope to have the book printed and ready for sale in fall 2023, with any proceeds going to the “Sustainability Exchange,” part of WashU’s Environmental Studies program, and Forest Park Forever, a nonprofit that helps sustain the park.]

“I proposed the project as an ode to Forest Park and WashU’s connection to it,” says Steensma, professor of practice in the Brown School. “I wanted to write a book about the biodiversity of the park — and about its import to the community. And I wanted the project to deeply involve students in the development and production of the book.”

It was Steensma, an ardent lover of nature and author of two books on birds, who first discussed the possibility of such a project with Jonathan Losos, the William H. Danforth Distinguished University Professor and director of the Living Earth Collaborative (LEC), and helped secure funding for its production by receiving an LEC grant in 2021.

“This was a dream project for me,” Johnson says. “Growing up, I was never indoors, and I lost a lot of that in college. I went to Forest Park, but it was nice to go and experience it in a different way, to be respectful of nature and the land — all while considering the concept of the book design. I’m trying to do the biodiversity justice and encapsulate as much of a range as possible.”

Tagging and tracking

Stella Uiterwaal, a community ecologist and biodiversity postdoctoral fellow at the Living Earth Collaborative, carries a handheld radio antenna listening for signals as she watches for any movement coming from the leaf-covered ground in Forest Park’s Kennedy Forest. On this spring day, Uiterwaal is searching, along with Jamie Palmer, a technician at the Institute for Conservation Medicine (ICM) at the Saint Louis Zoo, and three ICM interns (Katie Handler, Emily Lesniak and Ansley Petherick), for three-toed box turtles previously outfitted with small radio-tracking tags. The research team aims to unearth the turtles and then record their location data points. The information they glean will be added to the yearslong data collection on box turtle movement and space use throughout the park.

Missouri’s official state reptile is just one of the critters of interest for scientists within the Forest Park Living Lab (FPLL). A collaborative of six regional organizations — Forest Park Forever, the National Great Rivers Research and Education Center, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis Zoo, Washington University and the World Bird Sanctuary — the Forest Park Living Lab brings together experts in ecology, conservation medicine, education and park management to explore Forest Park’s urban ecosystem.

“The Living Lab will help us understand the ways in which Forest Park wildlife move through the human-dominated habitat, but it also paves the way with methods, data and general proof-of-concept for similar projects in other cities.”

Stan Braude

“Steve Blake [assistant professor of biology, Saint Louis University] and Sharon Deem [director of ICM at the zoo] have been studying the turtle population in Forest Park for years, and the Living Lab is an important extension of that work,” says Stan Braude, teaching professor of practice in biology in Arts & Sciences. “The Living Lab will help us understand the ways in which Forest Park wildlife move through the human-dominated habitat, but it also paves the way with methods, data and general proof-of-concept for similar projects in other cities.”

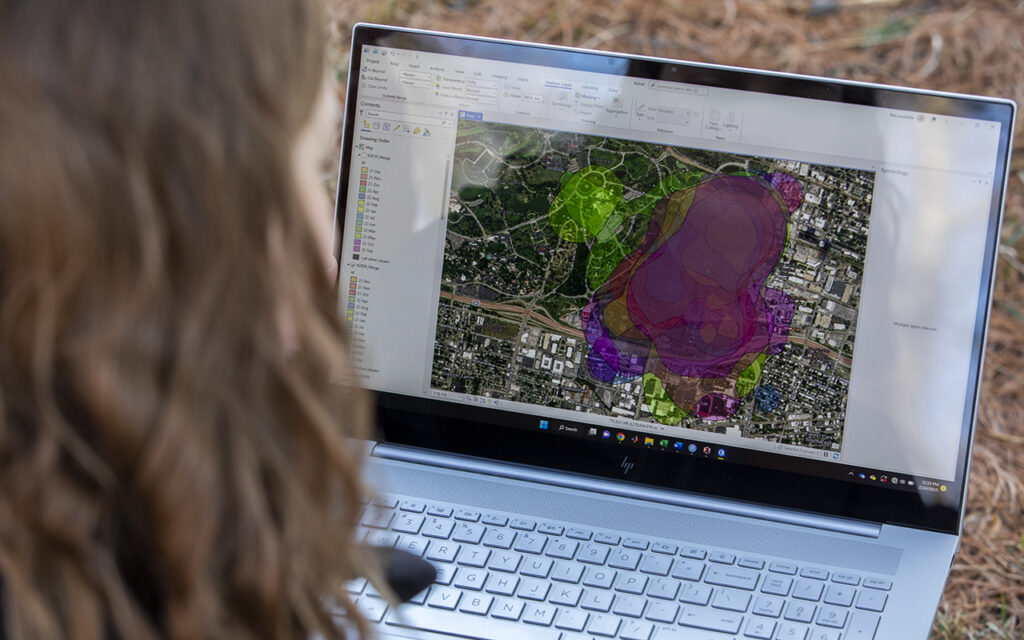

“We are tracking animals in the park to understand how urban wildlife interact with different habitats, with other animals in the ecological community and with the urban environment around them,” says Uiterwaal, a senior scientist for the FPLL. “We want to understand the movement of biodiversity across an entire food web, from herbivores to apex predators.” In addition, the Living Lab is collecting health data on Forest Park wildlife to understand disease dynamics, particularly in connection to movement and the animals’ urban setting.

To date, the Forest Park Living Lab, which is also sponsored by the Living Earth Collaborative, is tracking box turtles and snapping turtles, mallards, raccoons and a great-horned owl named Astrid. Researchers plan to tag coyotes, herons and egrets next, with an eventual intention to track some 17 species.

“I was brought in as a mammalogist with experience trapping various rodents in Africa and South America,” Braude says, “but team members of the Living Lab are very collaborative, and we’re all learning from one another, whether it’s conducting radio tracking, analyzing data or teaching classes in Forest Park.”

The country’s No. 1 park

As a WashU community member, you probably know that Forest Park — the “Best City Park” in the country, so recognized by USA Today’s 10 Best Readers’ Choice 2023 awards — hosts major cultural institutions: the Missouri History Museum, the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Saint Louis Science Center and, of course, the Saint Louis Zoo. You might have used the park’s tennis center, skating rink, golf courses, ballfields, miles of pathways and trails, and much more. What you may not know, though, is that Forest Park is home to more than 600 species of plants, 20 species of native fishes, 20 species of reptiles, 23 species of mammals, 200 species of pollinators (bees, butterflies, moths) and 200+ additional insect species, as well as 222 species of birds. And that’s outside the zoo!

“When you say you’re in something, that means you’re in community with something. I think this project provided a great opportunity to discover how to build community with these things that we’re taught are wild.”

Joe Steensma

The Forest Park Living Lab as well as the “Sustainability Exchange” book project allow for students and faculty to meaningfully engage with this bountiful biodiversity in new and unexpected ways.

“The Living Earth Collaborative is deeply invested and committed to involving and educating citizen-scientists,” Braude says, “and we have worked closely with the community from the beginning.”

“We had a number of different majors that came together to produce, curate and collate content for the book,” Steensma says. “At a fundamental level, our purpose was to expose students to the process of writing a book, but also more broadly to expose them to the connectness between biodiversity and people.”

Steensma says that he wanted to give students the time to be “in” Forest Park. “When you say you’re in something, that means you’re in community with something,” he continues. “I think this project provided a great opportunity to discover how to build community with these things that we’re taught are wild.”