Alzheimer’s disease starts with a sticky protein called amyloid beta that builds up into plaques in the brain, setting off a chain of events that results in brain atrophy and cognitive decline. The new generation of Alzheimer’s drugs — the first proven to change the course of the disease — work by tagging amyloid for clearance by the brain’s immune cells.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found a different and promising way to remove the noxious plaques: by directly mobilizing immune cells to consume them.

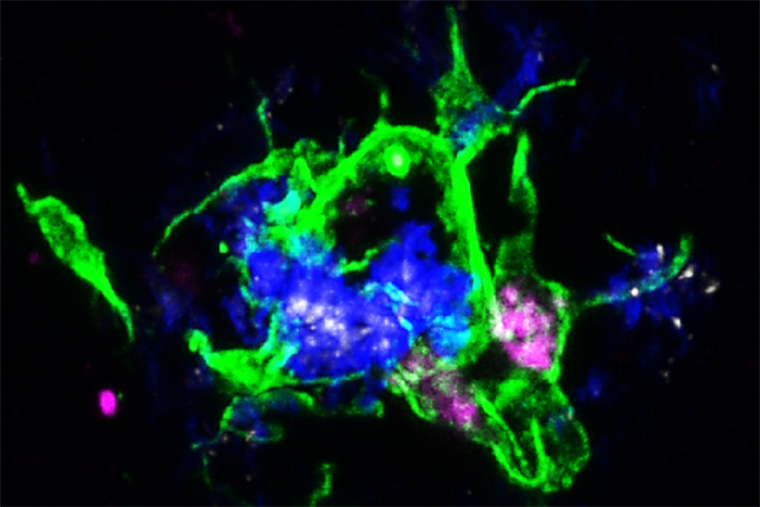

In a study published April 3 in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers showed that activating immune cells called microglia with an antibody reduces amyloid plaques in the brain and mitigates behavioral abnormalities in mice with Alzheimer’s-like disease.

The approach could have implications beyond Alzheimer’s. Toxic clumps of brain proteins are features of many neurodegenerative conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease. Encouraged by the study results, researchers are exploring other potential immunotherapies — drugs that harness the immune system — to remove junk proteins from the brain that are believed to advance other diseases.

“By activating microglia generally, our antibody can remove amyloid beta plaques in mice, and it could potentially clear other damaging proteins in other neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease,” explained the study’s senior author, Marco Colonna, MD, the Robert Rock Belliveau, MD, Professor of Pathology.

Microglia surround plaques to create a barrier that controls the damaging protein’s spread. They also can engulf and destroy the plaque proteins, but in Alzheimer’s disease they usually do not. The source of their passivity could result from a protein called APOE that is a component of amyloid plaques. The APOE proteins in the plaque bind to a receptor – LILRB4 – on the microglia surrounding the plaques, inactivating them, Yun Chen, co-first author on the study, explained.

For reasons that are still unknown, the researchers found that, in mice and people with Alzheimer’s disease, microglia that surround plaques produce and position LILRB4 on their cell surface, which inhibits their ability to control damaging plaque formation upon binding to APOE. The other co-first author Jinchao Hou, PhD, now a faculty member at Children’s Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in Zhejiang Province, China, treated mice that had amyloid beta plaques in the brain with a homemade antibody that blocked APOE from binding to LILRB4. After working with Yongjian Liu, PhD, a professor of radiology in Washington University’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, to confirm that the antibody reached the brain, the researchers found that activated microglia were able to engulf and clear the amyloid beta plaques.

Clearing the amyloid beta plaques in mice also alleviates risk-taking behavior. Individuals with AD may lack memory of past experiences to inform their decisions. They may engage in risky behavior, making them vulnerable to becoming victims of fraud or financial abuse. Treating mice with an antibody to clear the plaques showed promise in altering the behavior.

After amyloid beta plaques form in the brain, another brain protein — tau — becomes tangled inside neurons. In this second stage of the disease, neurons die and cognitive symptoms arise. High levels of LILRB4 and APOE have been observed in AD patients in this later stage, Chen explained. It is possible that blocking the proteins from interacting and activating microglia could alter later stages of the disease. In future studies, the researchers will test the antibody in mice with tau tangles.

Drugs that target amyloid plaques directly can cause a potentially serious side effect. In Alzheimer’s patients, amyloid proteins build up on the walls of the arteries in the brain as well as other parts of brain tissue. Removing plaques from brain blood vessels can induce swelling and bleeding, a side effect known as ARIA. This side effect is seen in some patients receiving lecanemab, a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat Alzheimer’s. The mice used in this study lacked amyloid plaques on blood vessels, so the researchers could not evaluate what happens when blood vessel plaques are removed.

They are working with a different mouse model — one that does have plaques on brain arteries — to understand if this new approach also carries a risk of ARIA.

“Lecanemab, as the first therapeutic antibody that has been able to modify the course of the disease, confirmed the importance of amyloid beta protein in Alzheimer’s disease progression,” said author David Holtzman, MD, the Barbara Burton and Reuben M. Morriss III Distinguished Professor of Neurology. “And it opened new opportunities for developing other immunotherapies that use different methods of removing damaging proteins from the brain.”

— Senior medical sciences writer Tamara Schneider contributed to this story.

Hou J, Chen Y, Cai Z, Heo GS, Yuede CM, Wang Z, Lin K, Saadi F, Trsan T, Nguyen AT, Constantopoulos E, Larsen RA, Zhu Y, Wagner ND, McLaughlin N, Kuang XC, Barrow AD, Li D, Zhou Y, Wang S, Gilfillan S, Gross ML, Brioschi S, Liu Y, Holtzman DM, Colonna M. Antibody-mediated targeting of human microglial leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 attenuates amyloid pathology in a mouse model. Science Translational Medicine. April 3, 2024. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adj9052

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers R24GM136766, RF1AG051485, R21AG059176, and AG078106; the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund; and Fred and Ginger Haberle Charitable Fund at East Texas Communities Foundation. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the NIH.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the School of Medicine website

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.