Growing up, Stephen Lockhart, MD, AB ’77, was struck by his mother’s deep interest in helping others achieve four-year degrees.

“Back then, she spent her life tirelessly teaching and getting babysitters and helping the students,” he notes about his mother, who was a mathematician with a graduate degree in urban planning from Washington University. Yet she was not able to find a suitable job in urban planning or mathematics until well into the 1970s, which made an impression on him, too.

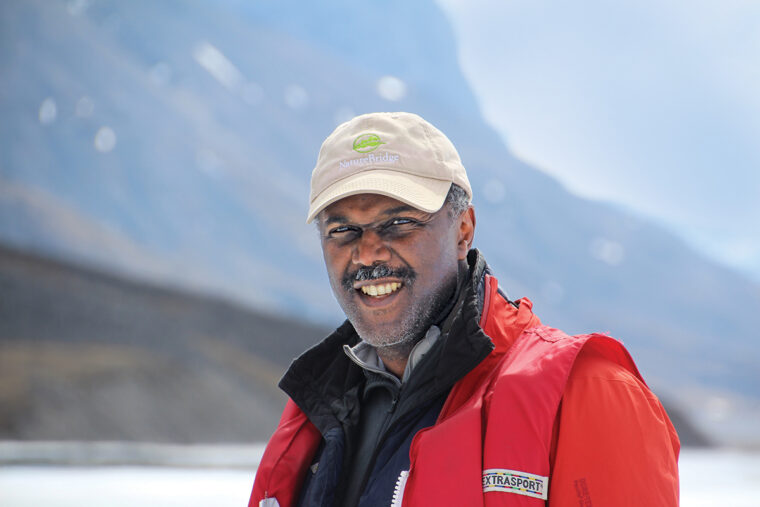

It’s no accident, he says, that he is involved in promoting education now. An avid climber and backpacker, Lockhart was named a Champion of Change by the White House in 2014 for his work supporting environmental education. He says he and others in such outdoors roles (such as friend Sally Jewell, 51st secretary of the interior) aim to create tomorrow’s conservation leaders.

Having learned about nature himself in a segregated Boy Scout troop in the St. Louis area, Lockhart noted in a talk at CleanMed 2017 (a national conference of health-care leaders in sustainability) that in the woods, “all those taboos and prohibitions and limitations that exist in our society simply didn’t exist in the outdoors. I found the outdoors to be invigorating, liberating and educational.”

Lockhart also works daily in science as an anesthesiologist and chief medical officer at California-based not-for-profit health-care system Sutter Health. His passion in promoting education in environmental science and introducing national parks to an increasingly diverse population shows up in his board memberships in cooperative outdoor retailer REI, the California-based organization NatureBridge, and prior membership in the National Parks Second Century Commission — a group of leaders and experts who convened in 2009, developed recommendations for the park service’s second century and presented findings to Congress, the Obama Administration and the American people.

With NatureBridge, he is involved with an organization that leads children on trips into six national parks, and it has exposed more than a million kids to environmental science since its founding in 1971. With such work, Lockhart says he aims to develop children’s critical thinking and “stop the degradation of science.” Along the way, outdoors leaders are created, he adds: One NatureBridge alum is the superintendent of Yosemite; and in the recent, hotly contested lawsuit over whether to dam the Merced River outside Yosemite, people on both sides of the lawsuit were former NatureBridge students. “We’re not telling them what to think; we’re asking them to know the issues, so they can talk about them,” Lockhart emphasizes.

With his mother’s interest in promoting knowledge still strong in his memory, he also supports scholarships for Washington University students. When his mother passed away in 1999, he says “it felt like the right thing to do” to fund an endowed scholarship in her name — Josephine Lockhart — to help students at Washington University, which she loved. Being a grad himself made that choice easy, too, he explains.

A strong humanities education at Washington University helped lead Lockhart toward the Rhodes Scholarship he received in 1977, he says. As someone who “studied a lot of medieval German courses, weird stuff that fascinated me,” and who eventually left for Oxford University to study for a master’s in economics, Lockhart says there is value in studying the arts and sciences as an undergraduate. “You meet lots of people doing many interesting things,” he says. “They become your friends, and your life is enriched by knowing people who study other areas.” That helped prepare him for conversations and hangouts at Oxford, where three of his economics professors later earned Nobel Prizes.

As the parent of a senior in high school, he passes on that recommendation to his daughter, telling her arts and sciences “is the place to start.” He thinks humanities make a person “better able to read the newspaper and understand what’s happening in the world. It makes you better-developed as you go into adulthood. ‘What is sociology?’ you might say randomly. ‘Let me take that and find out.’ The opportunities are so great.”