A curious boy from a small fishing village on the eastern coast of Taiwan, Ping Wang began his education with a passion for poetry. He dreamed of becoming a distinguished writer or a scholar of Chinese literature.

Decades later, Wang holds down a day job as a distinguished scholar of global economics at Washington University. He still writes poetry, and his love of the humanities continues to be the driving force behind his research into the forces that shape human welfare.

“When we look at economic issues, we cannot ignore cultural differences,” says Wang, PhD, the Seigle Family Professor in Arts & Sciences and the McDonnell International Scholar Academy’s ambassador to the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “When it comes to international trade, East Asian countries have a much different perspective than Latin American countries.

“Different cultures have different views about money and work habits. So, when I do economics, I also think a great deal about social issues, about larger global impacts, about how these factors change over time.”

Wang’s research explores social, political and cultural considerations that influence who wins and who loses in the global economic arena. His studies cover the gambit of human experience, delving into the economics of organized crime, the timing of childbearing and whether alcoholics are in bad jobs.

Last year, research took him to Belgium to examine the formation of research parks, to Hong Kong to study lingering economic effects of British colonization, and to Taiwan for two projects on human capital formation. In an Italian town known as a hotbed for organized crime, he lectured on effective strategies for curtailing criminal operations. The setting, he admits, was a bit intimidating.

Like his journey to Washington University, Wang’s academic career has followed a long and circuitous global path.

Transitional economics

In high school, counselors were so impressed with Wang’s scores in math and science they pressured him to leave the arts and accept placement in a top engineering program. Wang complied, setting out for a degree in ocean transportation.

“Within a year, I begin to feel that this is not a match with my interests,” he says. “I just feel bored. Not because it is unimportant. Taiwan is an island with strong international trade, so ships and ports are important to us. Problem is, I always have a strong passion for literature, for humanities. Engineering was too cold and hard for me. My heart could not touch it.”

Luckily, Wang opted into an applied economics course, his university’s only economics offering. His math skills were well-suited to economics and, inspired by his professor, he found a new passion. Forced to find economics courses elsewhere, he spent a couple days each week at three universities, graduating from two of them with a bachelor’s degree in ocean transportation and a master’s degree in economics.

Along with his wife and young child, Wang moved to New York to study at the University of Rochester under the mentorship of Marcus Berliant, PhD, an economics professor now at Washington University. He defended his dissertation a week before his wife had their second child. He missed his graduation ceremony to remain by her side.

In 1986, he began teaching at Penn State University, where he discovered American football and his wife pursued a master’s in fine art. He embraced the quiet Pennsylvania campus for its sports connections and safe neighborhoods, perfect for raising children.

Penn State maintained its hold on Wang for more than a decade. He left on occasion for high-profile positions at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Purdue University and the University of Washington in Seattle. But he always returned within a year to resume life at Penn State. Finally, in 1999, after his wife completed her degree, Wang left Penn State to join the faculty at Vanderbilt University.

Intellectual property

His many articles include paradigm-shifting research on international business cycles in American Economic Review and a well-regarded two-sector model for comparing the growth of physical and human capital in economic transition in the Journal of Economic Theory. His study of public policy in perpetually growing economies with labor market barriers is forthcoming in the International Economic Review.

Courtesy photo

(From left) Ping Wang, daughters Clarice and Beatrice, and wife, Teresa, vacationing in Italy last summer. The trip was a family capstone to Wang’s world travels as part of his yearlong research sabbatical.

“Ping is one of the most diverse economists around, and the scope of his work is truly remarkable,” says Gaetano Antinolfi, PhD, WUSTL associate professor of economics. “Few can claim to have succeeded in using economic theory in such a far-reaching and prolific way.”

His theoretical work in the realm of dynamic general equilibrium spans such disciplines as monetary economics, labor economics, growth and development, international trade, business cycles, health economics and economic geography. His studies range from the structure of cities to the history of Chinese hyperinflation to the implications of addiction for public policy and economic growth.

“His range of topics clearly reflects the broad intellectual curiosity that Ping naturally possesses,” Antinolfi says. “The unifying theme of all his research is an interest in the rigorous exploration of the policies that are important to the well-being of human beings, whether they be social policies, monetary policies or environmental policies.”

Wang’s visiting faculty positions also span the globe, from Tilburg University in the Netherlands to Kobe and Kyoto universities in Japan to the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He has been a visiting scholar at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan since 1994 and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research since 2001.

Competitive marketplace

His reputation as a highly successful recruiter of top-notch economics faculty, honed first at Penn State and later at Vanderbilt, was a critical factor in Washington University’s decision to lure him to St. Louis in 2005 to serve as chair of economics.

WUSTL, as part of a review process, had singled out economics for major expansion as part of a larger effort to build on strengths in interdisciplinary social sciences research. Wang’s experience made him a perfect choice to lead recruitment of world-class economic scholars.

“The one single thing people ought to know about Ping’s three years as chair is that he executed his build-up plan almost to the letter,” says John Nachbar, PhD, professor and associate chair of the economics department. “The plan called for hiring 12 faculty over three years, and we hired exactly 12 faculty. And the outcome, in terms of the quality of the hires, was, if anything, better than we ever could have hoped.”

Nachbar attributes Wang’s recruitment success to a number of traits that also made him an effective departmental chair. Highly organized with high ambitions for the department, he has a detailed practical knowledge of how the economic job market works, including a wide network of professional contacts, which is crucial for identifying top candidates.

Building human capital

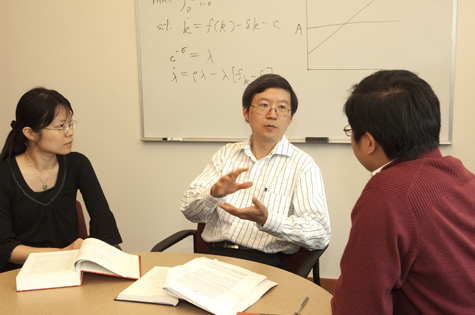

And, he’s also a hard worker. One colleague jokes that “Ping never sleeps.” One of his graduate students, Yin-Chi Wang, says he’s known as the 7-11 professor, a nickname based on his habit of working from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m.

“He really exerts a lot of effort in his teaching, and he cares a lot about his students, both in their research and in their lives,” Yin-Chi says. “He is always cheerful and energetic, and always laughs loudly. He seems able to transmit this cheerfulness to others.”

Burak Uras, another of Wang’s doctoral advisees, will graduate this spring with an offer to join the prestigious economics faculty at Tilburg University in the Netherlands. Uras attributes much of his doctoral success to Wang’s warm and patient guidance:

“Ping helped me to develop my economic insight by showing me, in his own words, that ‘fundamentals matter the most’ for economic analysis. He taught me how to think about economically significant questions.”

Uras also credits Wang with helping him survive the dissertation process, describing his guidance as being of “great value” to his personal and academic development.

“I think of him as a distinguished mentor for his constant encouragement and for making me believe in myself throughout my doctoral studies,” Uras says. “I have truly enjoyed learning from him as a doctoral student.”

Household dynamics

Wang’s children, now living on their own, also are pursuing advanced degrees in the sciences. Asked if he ever had to talk his own children out of pursuing a degree in Chinese literature, Wang laughs.

“No. Never. I was talked out of doing what I liked, so I would never dream of putting such pressure on my children,” he says. “I allowed them all the freedom to choose whatever the field, whichever the school, they desired.”

Wang’s older daughter, Beatrice, is a doctoral student in biomedical research at the University of California, San Francisco. His younger, Clarice, a recent graduate of Washington University, is a first-year clinical neuropsychology doctoral student at the University of Kansas, the school Wang picked to win the men’s NCAA basketball championship.

Kansas failed to make it into the tournament’s “Sweet 16” elimination bracket, but his pick to face Kansas in the finals, Duke University, won the tournament. All and all, Wang is proud he picked the winner in 61 percent of games played.

Although he’s well-settled in St. Louis, Wang remains a fan of the Pittsburgh Steelers, a habit he picked up at Penn State.

Teresa, his wife of 28 years, now works as an independent arts educator and painter based in a small studio in their home, located a couple miles from campus in Clayton.

Wang describes her work as bridging the cultures of East and West, using oils, watercolors and other standard techniques of Western painting to render images drawn from Chinese, Japanese and Thai cultures.

“Her work, to me, is very creative and beautiful,” Wang says warmly. “She has been with me through everything, my entire career. I would not be here without her support and understanding.”

Fast facts about Ping Wang

Born: 1957, in Taiwan

Education: BS, 1979, ocean transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan; MA, 1981, economics, National Chengchi University, Taiwan; MA, 1986, PhD, 1987, economics, University of Rochester

Hobbies: Basketball and football sports fan; American Contract Bridge League, Grand Life Master and one-time North American champion; and poetry for publication in Chinese newspapers and magazines

Favorite poets: Dante and the eighth-century Chinese poet Bai Li